Crash site investigation with drones has emerged as a leading application for unmanned systems in public safety. Gathering data that can be used by investigators in a courtroom, however, requires careful mission planning. Here, sUAS expert and industry figure Douglas Spotted Eagle of Sundance Media provides a detailed insider’s view of a helicopter crash site investigation.

Guest post by Douglas Spotted Eagle, Founder and Director of Educational Programming at Sundance Media Group. DRONELIFE neither accepts nor makes payment for guest posts.

Unmanned aircraft have become proven assets during investigations, offering not only the ability to reconstruct a scene. When a high ground sampling distance (GSD) is used, the data may be deeply examined, allowing investigators to find evidence that may have not been seen for various reasons during a site walk-through.

Recently, David Martel, Brady Reisch and I were called upon to assist in multiple investigations where debris was scattered over a large area, and investigators could not safely traverse the areas where high speed impacts may have spread evidence over large rocky, uneven areas. In this particular case, a EuroStar 350 aircraft may have experienced a cable wrap around the tail rotor and boom, potentially pulling the tail boom toward the nose of the aircraft, causing a high speed rotation of the hull prior to impact. Debris was spread over a relatively contained area, with some evidence unfound.

“The helicopter was on its right side in mountainous densely forested desert terrain at an elevation of 6,741 ft mean sea level (MSL). The steel long line cable impacted the main rotor blades and was also entangled in the separated tail rotor. The tail rotor with one blade attached was 21 ft. from the main wreckage. Approximately 30 ft. of long line and one tail rotor blade were not located. The vertical stabilizer was 365 ft. from the main wreckage.”

With a missing tail rotor blade and the missing long line, unmanned aircraft were called in to provide a high resolution map of the rugged area/terrain, in hopes of locating the missing parts that may or may not aid in the crash investigation.

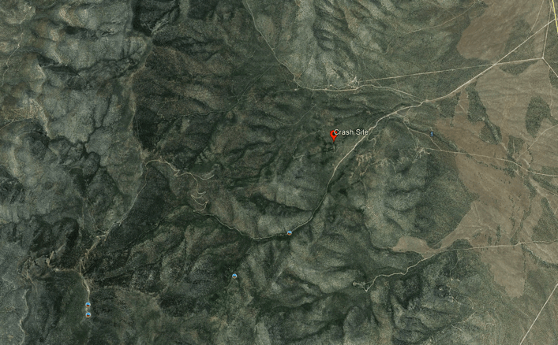

The terrain was difficult and unimproved, requiring four-wheel drive vehicles for access into the crash site. Due to rising terrain, we elected to launch/land the aircraft from the highest point relevant to the crash search area, which encompassed a total of approximately 70 acres.

Adding to the difficulty of finding missing parts was that the helicopter was partially covered in grey vinyl wrap, along with red and black vinyl wrap, having recently been wrapped for a trade show where the helicopter was displayed.

We arrived on scene armed with pre-loaded Google Earth overheads, and an idea of optimal locations to place seven Hoodman GCP discs, which would allow us to capture RTK points for accuracy, and Manual Tie Points once the images were loaded into Pix4D. We pre-planned the flight for an extremely high ground sampling distance (GSD) average of .4cm per pixel. Due to the mountainous terrain, this GSD would vary from the top to the bottom of the site. We planned to capture the impact location at various GSD for best image evaluation, averaging as tight as .2cmppx. Some of these images would be discarded for the final output, and used only for purposes of investigation.

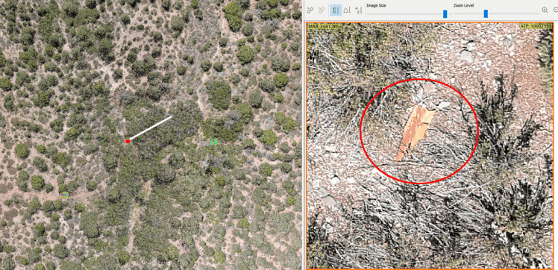

Although the overall GSD was greater than necessary, the goal is to be able to zoom in very deep on heavily covered areas with the ability to determine the difference between rocks and potential evidence, enabling investigators to view the overall scene via a 3.5 GB GeoTiff in Google Earth, and refer back to the Pix4DMapper project once rendered/assembled.

The same scene minus initial marker points.

Although working directly in Pix4D provides the best in-depth view of each individual photo, the Google Earth overlay/geotiff enables a reasonably deep examination.

Using two of the recently released Autel EVO II Pro aircraft, we planned the missions so that one aircraft would manage North/South corridors while the other captured East/West corridors. Planning the mission in this manner allows for half the work time, while capturing the entire scene. This is the same method we used to capture the MGM festival grounds following the One October shooting in Las Vegas, Nevada. The primary difference is in the overall size, with the Pioche mission being nearly 70 acres, while the Las Vegas festival ground shooting area is under 20 acres in total.

Similar to the Las Vegas shooting scene, shadow distortion/scene corruption was a concern; flying two aircraft beginning at 11:00 a.m. and flying until 1:30 aided in avoiding issues with shadow.

Temporal and spatial offsets were employed to ensure that the EVO II Pro aircraft could not possibly collide, we set off at opposite sides of the area, at different points in time, with a few feet of vertical offset added in for an additional cushion of air between the EVO II. We programmed the missions to fly at a lower speed of 11 mph/16fps to ensure that the high GSD/low altitude images would be crisp and clean. It is possible to fly faster and complete the mission sooner, yet with the 3 hour travel time from Las Vegas to the crash site, we wanted to ensure everything was captured at its best possible resolution with no blur, streak, or otherwise challenged imagery. Overall, each aircraft emptied five batteries, with our batteries set to exchange notification at 30%.

Total mission running time was slightly over 2.5 hours per aircraft, with additional manual flight over the scene of impact requiring another 45 minutes of flight time to capture deep detail. We also captured imagery facing the telecommunications tower at the top of the mountain for line of sight reference, and images facing the last known landing area, again for visual reference to potential lines of sight.

By launching/landing from the highest point in the area to be mapped, we were able to avoid any signal loss across the heavily wooded area. To ensure VLOS was maintained at all times, FoxFury D3060’s were mounted and in strobing mode for both sets of missions (The FoxFury lighting kit is included with the Autel EVO II Pro and EVO II Dual Rugged Bundle kits).

Once an initial flight to check exposure/camera settings was performed, along with standard controllability checks and other pre-flight tasks, we sent the aircraft on their way.

Capturing over 6000 images, we checked image quality periodically to ensure consistency. Once the missions were complete, we drove to the site of impact to capture obliques of the specific area in order to create a more dense model/map of the actual impact site. We also manually flew a ravine running parallel to the point of impact to determine if any additional debris was found (we did find several small pieces of fuselage, tools assumed to be cast off at impact, and other debris.

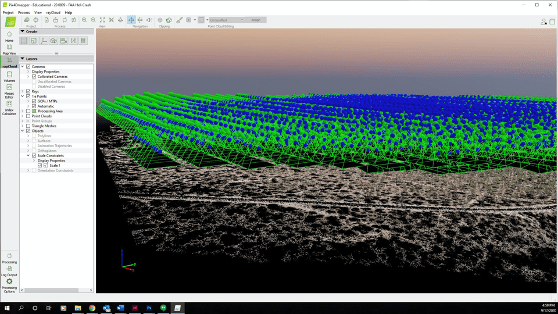

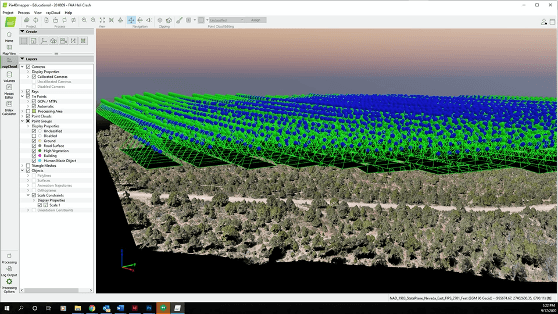

The initial pointcloud took approximately 12 hours to render, generating a high-quality, highly dense initial cloud.

After laying in point controls, marking scale constraints as a check, and re-optimized the project in Pix4D, the second step was rendered to create the dense point cloud. We were stunned at the quality of the dense point cloud, given the large area.

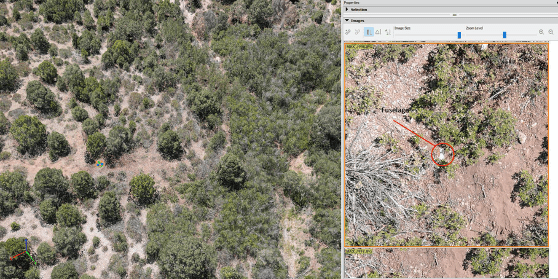

The dense point cloud is ideal for purposes of measuring. Although this sort of site would typically benefit (visually) from texturing/placing the mesh, it was not necessary due to the high number of points and deep detail the combination of Pix4D and Autel EVO II Pro provided. This allowed us to select specific points where we believed points of evidence may be located, bringing up the high resolution images relevant to that area. Investigators were able to deep-dive into the area and locate small parts, none of which were relevant to better understanding the cause of the crash.

“The project generated 38,426,205 2D points and 13,712,897 3D points from a combination of nearly 7,000 images.”

Using this method of reviewing the site allows investigators to see more deeply, with ability to repeatedly examine areas, identify patterns from an overhead view, and safely search for additional evidence that may not be accessible by vehicle or foot. Literally every inch of the site may be gone over.

Further, using a variety of computer-aided search tools, investigators may plug in an application to search for specific color parameters. For example, much of the fuselage is red in color, allowing investigators to search for a specific range of red colors. Pieces of fuselage as small as 1” were discovered using this method. Bright white allowed for finding some items, while 0-16 level black allowed for finding other small objects such as stickers, toolbox, and oil cans.

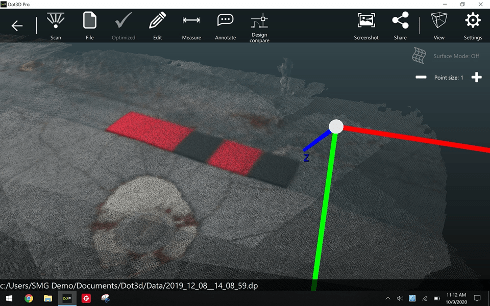

Using a tool such as the DTResearch 301 to capture the RTK geolocation information, we also use the DTResearch ruggedized tablet as a localized pointcloud scan which may be tied into the Pix4Dmapper application. Capturing local scan data from a terrestrial perspective with GCP’s in the image allow for extremely deep detail in small environments. This is particularly valuable for construction sites or interior scans, along with uses for OIS, etc.

Primary Considerations When Capturing a Scene Twin

Primary Considerations When Capturing a Scene Twin

- GSD. This is critical. There is a balance between altitude and propwash, with all necessary safety considerations.

Vertical surfaces. In the event of an OIS where walls have been impacted, the ability to fly vertical surfaces and capture them with a consistent GSD will go a long way to creating a proper model. Shadow distortion. If the scene is very large, time will naturally fly by and so will the sun. In some conditions, it’s difficult to know the difference between burn marks and shadows. A bit of experience and experimentation will help manage this challenge. - Exposure. Checking exposure prior to the mission is very important, particularly if an application like Pix4Dreact isn’t available for rapid mapping to check the data on-site.

Angle of sun/time of day. Of course, accidents, incidents, crime, and other scenes happen when they happen. However, if the scene allows for capture in the midday hours, grab the opportunity and be grateful. This is specifically the reason that our team developed night-time CSI/Datacapture, now copied by several training organizations across the country over recent years. - Overcapture. Too much overlap is significantly preferable to undercapture. Ortho and modeling software love images.

- Obliques. Capture obliques whenever possible. Regardless of intended use, capture the angular views of a scene. When possible, combine with ground-level terrestrial imaging. Sometimes this may be best accomplished by walking the scene perimeter with the UA, capturing as the aircraft is walked. We recommend removing props in these situations to ensure everyone’s safety.

What happens when these points are put aside?

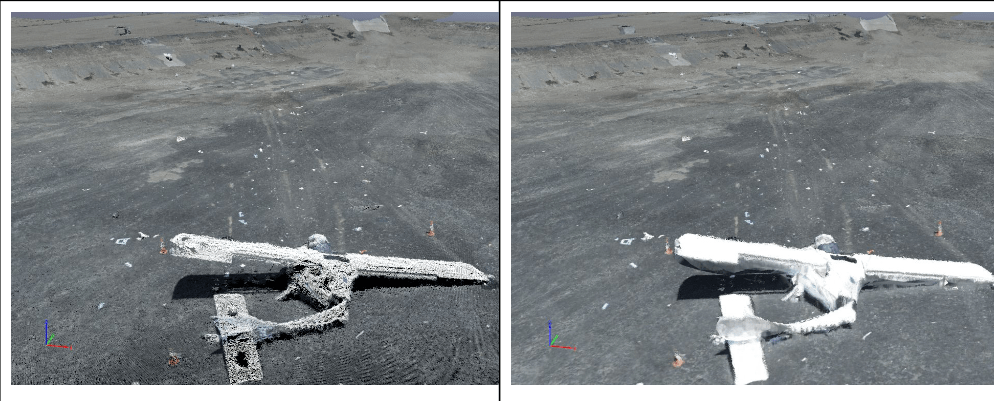

This is a capture of a scene brought to us for “repair,” as the pilot didn’t know what he didn’t know. Although we were able to pull a bit of a scene, the overexposure, too-high altitude/low GSD, and lack of obliques made this scene significantly less valuable than it might have been.

Not understanding the proper role or application of the UA in the capture process, the UA pilot created a scene that is difficult to accurately measure, lacking appropriate detail, and the overexposure creates difficulties laying in the mesh. While this scene is somewhat preserved as a twin, there is much detail missing where the equipment had the necessary specifications and components to capture a terrific twin. Pilot error cannot be fixed. Operating on the “FORD” principle, understanding that FOcus, exposuRe, and Distance (GSD) cannot be rectified/compensated for in post processing means it has to be captured properly the first time. The above scene can’t be properly brought to life due to gross pilot error.

“ALWAYS PUT THE AIRCRAFT OVER THE PRIMARY SCENE LOCATION TO CONFIRM EXPOSURE SETTINGS, KEEPING ISO AS LOW AS POSSIBLE. USE ISO 50-100 IN MOST OUTDOOR SCENARIOS TO OBTAIN THE BEST IMAGE. NEVER USE OVERSATURATED PHOTO SETTINGS OR LOG FORMATS FOR MAPPING.”

Ultimately, the primary responsibility is to go beyond a digital twin of the scene, but instead offer deep value to the investigator(s) which may enhance or accelerate their investigations. Regardless of whether it’s a crash scene, insurance capture, energy audit, or other mapping activity, understanding how to set up the mission, fly, process, and export the mission is paramount.

Capturing these sorts of scenes are not for the average run n’ gun 107 certificate holder. Although newer pilots may feel they are all things to all endeavors benefitting from UA, planning, strategy, and experience all play a role in ensuring qualified and quality captures occur. Pilots wanting to get into mapping should find themselves practicing with photogrammetry tools and flying the most challenging environments they can find in order to be best prepared for environmental, temporal, and spatial challenges that may accompany an accident scene. Discovery breeds experience when it’s cold and batteries expire faster, satellite challenges in an RTK or PPK environment, planning for overheated tablets/devices, managing long flight times on multi-battery missions, or when winds force a crabbing mission vs a head/tailwind mission. Learning to maintain GSD in wild terrain, or conducting operations amidst outside forces that influence the success or failure of a mission only comes through practice over time. Having a solid, tried and true risk mitigation/SMS program is crucial to success.

We were pleased to close out this highly successful mission, and be capable of delivering a 3.5 GB geotiff for overlay on Google Earth, while also being able to export the project for investigators to view at actual ground height, saving time, providing a safety net in rugged terrain, and a digital record/twin of the crash scene that may be used until the accident investigation is closed.

EQUIPMENT USED

● 2X Autel EVOII™ Pro aircraft

● Autel Mission Planner software

● FoxFury D3060 lighting

● DTResearch 301 RTK tablet

● Seko field mast/legs

● Seko RTK antenna

● Hoodman GCP

● Hoodman Hoods

● Manfrotto Tripod

● Dot3D Windows 10 software

● Pix4DMapper software

● Luminar 4 software

Douglas Spotted Eagle is the Founder and Director of Educational Programming at Sundance Media Group. SMG serves as a consultant within the sUAS industry, offering training and speaking engagements on sUAS topics: UAV cinematography, commercial and infrastructural sUAS applications, sUAS risk management, night UAV flight, aerial security systems, and 107 training.

Douglas Spotted Eagle is the Founder and Director of Educational Programming at Sundance Media Group. SMG serves as a consultant within the sUAS industry, offering training and speaking engagements on sUAS topics: UAV cinematography, commercial and infrastructural sUAS applications, sUAS risk management, night UAV flight, aerial security systems, and 107 training.

Miriam McNabb is the Editor-in-Chief of DRONELIFE and CEO of JobForDrones, a professional drone services marketplace, and a fascinated observer of the emerging drone industry and the regulatory environment for drones. Miriam has penned over 3,000 articles focused on the commercial drone space and is an international speaker and recognized figure in the industry. Miriam has a degree from the University of Chicago and over 20 years of experience in high tech sales and marketing for new technologies.

For drone industry consulting or writing, Email Miriam.

TWITTER:@spaldingbarker

Subscribe to DroneLife here.

[…] and Look-Up Tables (LUTS.). (See more of Douglas Spotted Eagle’s in-depth work on DRONELIFE here and here.)Guest post by Douglas Spotted Eagle, Founder and Director of Educational Programming at […]