Scott Jackman of Fly Ag Tech shares his story and key tips for building a drone business

Drone enthusiasts know that there’s big potential for drones to bring value to wide a range of industries. But when thinking about how to turn your hobby into a business — it can be hard to know where to start.

With that in mind, we’d like to introduce Scott Jackman, co-founder and COO of Kansas City Drone Company, to share his story and outline four key steps for building a drone business.

Kansas City Drone Company was started by Casey Adams and Scott Jackman. Casey worked as a drone contractor for the Department of Defense. Scott was raised a farmer and retired from the Army as a Lieutenant Colonel and a reconnaissance helicopter pilot. With roots in farm country, they saw the value that drones can provide, and decided that it made perfect sense to use their expertise from the military to help farm owners and other businesses improve their processes. Today, Fly Ag Tech, the agriculture-focused division of Kansas City Drone Company, is the nation’s largest network of agriculture-focused drone operators and agronomists.

Understand the Business You’re Trying to Help

Scott: Anyone who wants to start a drone company or operate in this business needs to focus on how to help business owners improve their operations, and to do that well, you need to understand what matters to them.

Farmers want to grow crops more efficiently. The manufacturing cost per acre on a farm ranges from $400–800 per acre. You need to be able to tell them how can you either reduce their production costs, increase their yield, or both.

I never tell our producers we will save them money, because sometimes the data might tell them to put more nitrogen on the corn. Instead, we tell our producers that we strive to improve their bottom line.

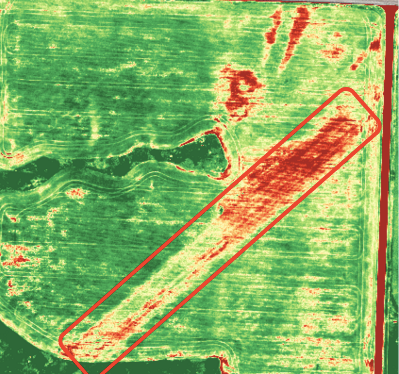

Drones offer a lot of opportunities to help producers improve their processes. They can help with variable rate nitrogen applications, crop scouting, disease mitigation, and stand counts — and new uses will continue to emerge over time. For example, one of our customers discovered that a utility company did not return his land to its original condition as stated in the contract.

We did not know we would find this. It emerged from the maps and our analysis. Another customer discovered his irrigation pivot was leaking water. He was paying for this wasted water.

2. Know What Value You Can Provide

Scott: Any drone service provider must understand the value he wants to provide to the customer. Customers hire drone service providers because they don’t want to maintain a drone fleet, deal with the FAA, and deal with the learning curve.

A picture, video, or map is of no value unless you can put it into context for the customer.

In the case of Fly Ag Tech, our unique value comes from being a network of drone operators. An individual drone operator is limited by how far he can drive in a single day to do a job and remain profitable, so he can only service and learn from a limited amount of jobs in a single growing season.

Our network of drone operators will have many more flight and crop analysis iterations per season than any one individual operator. This will ensure our teammates are able to learn more rapidly.

Fly Ag Tech doesn’t just fly and capture imagery. We also provide insights from aerial data to help aid in planting, fertilizing and harvesting, and partner with agronomists to help interpret NDVI maps and translate insight into precision ag software.

3. Consider the Logistics

Scott: Take the time to understand air space, weather and aerodynamics. If you operate a drone as a business, you will be putting yourself and your equipment into this environment every day.

Do some research on how to run a company that has equipment and/or aircraft.

Your aircraft, batteries, cameras, and software will degrade or become obsolete over time — all factors you’ll need to incorporate into your pricing structure to ensure you can eventually make a profit. Otherwise, you are simply doing a hobby full time.

Conduct your flight operations legally and safely. Always be safety conscious and err on the side of safety to protect your client, your employees, your equipment, and non-participants. Most construction companies require OSHA certification. Safety is not optional.

4. Get Out There and Fly!

Scott: There are five things you need to start flying your drone commercially.

- A drone

- Mapping software

- Pilot’s license

- 333 exemption

- A network of people who can help you analyze data, learn and grow.

Get out and network. Talk with other drone companies in your area or join a local AUVSI chapter. Consider starting as a drone operator for an existing company — this can be a great way to learn about the industry and processes. Talk with business owners and ask how they think drones could help them. Get out of the office. Clients are out in the world, not in your office.

— –

Fly Ag Tech is actively seeking drone operators who love Ag, love drones and want to learn from a network of other Ag operators. Interested in joining the team? Contact scott@kcdroneco.com.

Frank Schroth is editor in chief of DroneLife, the authoritative source for news and analysis on the drone industry: it’s people, products, trends, and events.

Email Frank

TWITTER:@fschroth

I want to get involved in the DERONE business I just don’t know where to start. Need all the help I can get.

Thank You

Raoul

#3 is extremely broad and is pretty much applicable to every single industry. Even if you’re an accountant that runs your own company, your technology is going to need updated and replaced eventually, just like office supplies. Factoring that into your pricing structure is common sense.

Thanks for the comment. I agree with you. However, many people who are trying to break into the drone industry are new and young sole proprietors who have never ran a business. My goal is to help them get going.