Bug Bounty programs are interesting, complex arrangements. In a way, they are an admission that every company building software is fallible and that mistakes can and will inevitably be made. They represent a well-established opportunity for collaboration between software companies and security researchers to prepare for that eventuality.

But that relationship is precarious. Bug Bounties are, after all, little more than a bribe negotiated between the two parties. A researcher will discover a vulnerability and the company impacted will pay for that issue to be kept quiet until it’s been resolved, as well as turn a blind eye toward how it was found in the first place.

So it goes without saying that Bug Bounty programs tend to have an interesting power dynamic. Huge companies are on one side and individual researchers are on the other. It’s up to both to behave ethically during the arrangement.

Which is where we come to DJI, the popular drone manufacturer that launched a Bounty program back in August. Usually, Bug Bounty programs are a preventative measure, the kind of thing a company puts in place to ensure they never have to deal with the PR fallout of a negative data security story. But in the case of DJI the move was reactive: the result of a summer of concerns about data security and weaknesses in the company’s software.

Putting Together a Bug Bounty Program in a Panic

Starting in July, it became clear that a drone jailbreaking scene was developing, with hackers finding ways to circumvent DJI’s built-in safety features – including GEO, the system designed to prevent pilots from flying above the legal limit and in restricted airspace. There were multiple stories of airport near misses and, presumably, many of those involved DJI aircraft. Then there were the probably not unconnected reports of the US and Australian militaries grounding DJI equipment over concerns regarding ‘cyber vulnerabilities’.

On top of that, there were elements of code – since rectified – found in DJI applications that were suspicious at best.

Understandably, all of this led to a range of measures from the Chinese manufacturer as part of a wider strategy to reassure customers that their data and drones were secure. One of these measures was the Bug Bounty program, set up to foster a more positive relationship with the security community, which had until then been both critical of DJI software and actively exploiting it.

On the face of it, the Bug Bounty program was, and remains, a positive step. And it was a sensible one that any company in DJI’s position should be making. The intentions were good: find the bugs, fix the bugs and reward ethical hackers for highlighting issues in the right way.

But the relationship between company and security researchers was always going to be precarious for two reasons. On the one hand, many of the hackers going after bounties were the same ones actively exploiting vulnerabilities in DJI’s software to customize their flying experience.

As one researcher, David Kovar, pointed out, “this group consists of very legitimate cybersecurity researchers. They were not seeking to make money, they were practising their craft on an ecosystem they are passionate about. A fairly traditional way for firms to keep disclosures from going public is via a bug bounty program, which this group tried to help them, DJI, establish.”

Kovar’s final point is the second reason that relationship was and remains so precarious. Essentially, DJI was making up the Bounty program as it went along with the help of the same external security researchers. The result was that bounty reports were submitted before researchers had any idea about the terms and conditions they were signing up to.

I asked two researchers who submitted bounties why they had done so before the terms of the agreement were clear. They made the point that big companies – The likes of Apple, Uber and United Airlines all have similar schemes in place – are usually trustworthy when it comes to paying out bounties and crediting the source of the fixed vulnerability. There was also an acceptance that DJI was new to the scene and that a certain level of patience was required.

Walking Away From the Bounty

DroneLife understands that the majority of researchers offered bounties by DJI after submitting successful reports have decided to walk away from the agreement. This is because the terms of the NDA – offered in retrospect by DJI – have been deemed unacceptable. It’s also related to a sudden threat of legal action with regards to the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act that understandably soured what was looking like a positive working relationship.

One thing researchers want when putting their necks on the line to find security issues is protection. You don’t want to get sued for essentially helping out a corporate giant, and you don’t want to hold any kind of liability moving forward once the bug has been reported and fixed. It’s also standard practice to be credited for the finding.

Researcher Kevin Finisterre, who was offered $30,000 for his bounty report, had the following to say in a document he published last night:

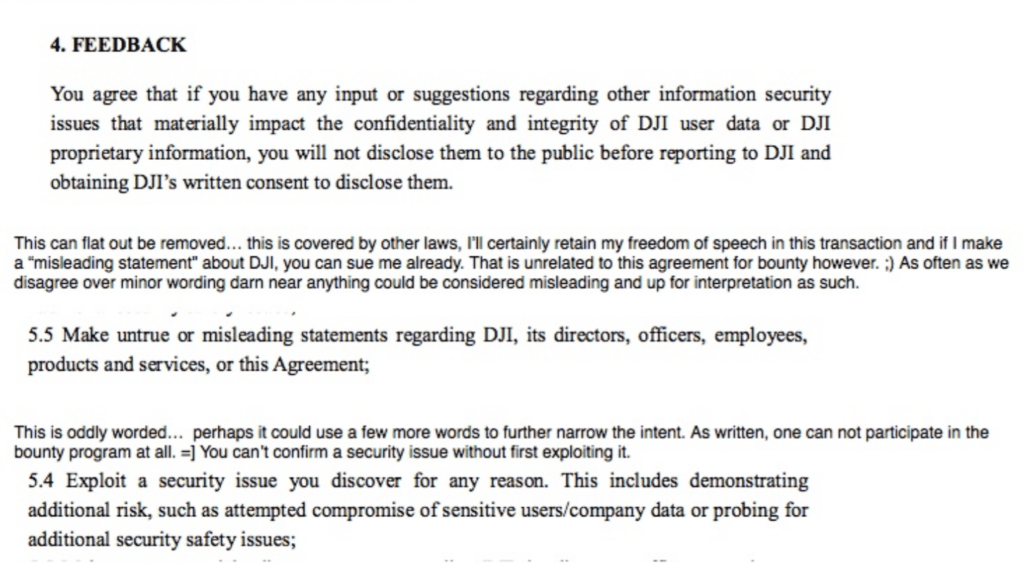

I won’t go into too much detail, but the agreement that was put in front of me by DJI in essence did not offer researchers any sort of protection. For me personally the wording put my right to work at risk, and posed a direct conflicts of interest to many things including my freedom of speech. It almost seemed like a joke. It was pretty clear the entire ‘Bug Bounty’ program was rushed based on this alone.

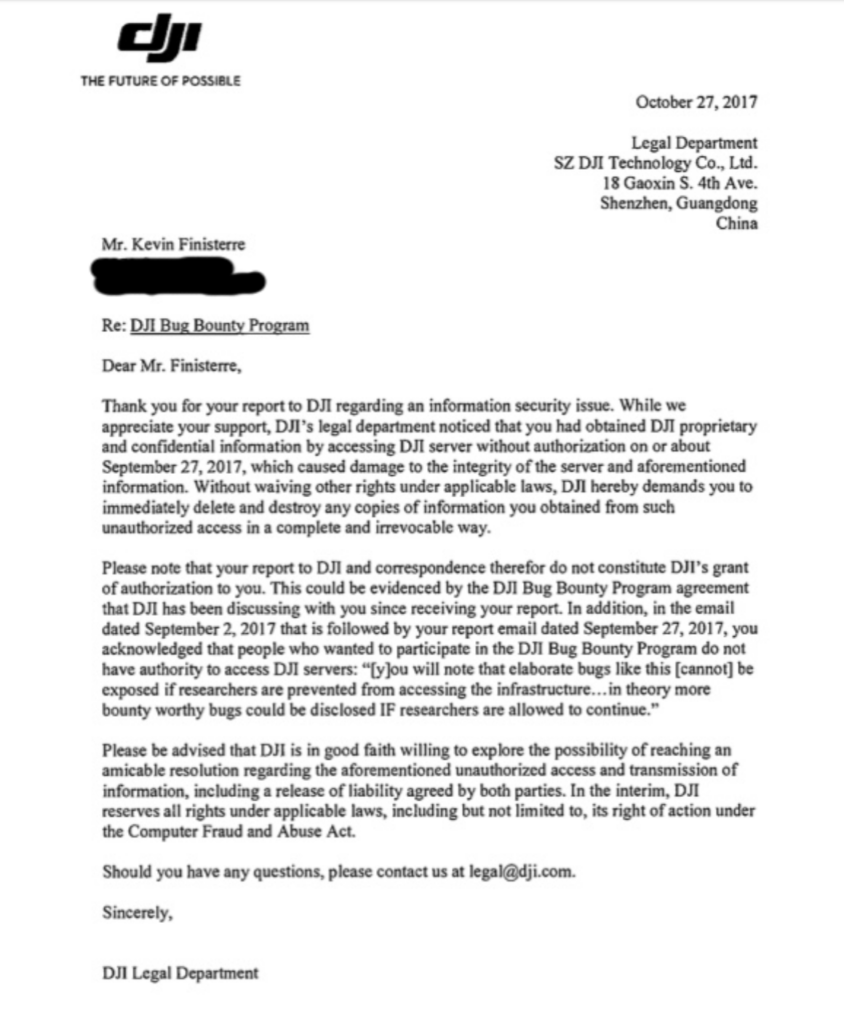

Several progressions were made in making the wording more acceptable, I must actually credit Brendan Schulman on attempting to serve as a communication bridge between myself and his Chinese counterparts in the legal department in Guangdong. Unfortunately he was not able to keep the barbarians at the gate, and I received a thinly veiled Computer Fraud and Abuse Act threat from DJI.

A Collision of Cultures?

It’s difficult to know where the responsibility lies for the complications that have arisen with DJI’s Bug Bounty program. From the emails highlighted in Finisterre’s report, it appears as though DJI’s Brendan Schulman is in a difficult position: trying to find the right balance between an agreement that will satisfy both his employers in Shenzhen and the security researchers ostensibly doing his company a favor. The fact that the CFAA legal threat (below) came directly from China is a case in point.

The fact that it was sent while NDA negotiations were ongoing says a lot.

The above letter could be viewed as a move to pressure Finisterre into signing the Bounty agreement. We don’t know if that’s the case, but in his own words, the NDA “was not only extremely risky, but was likely crafted in bad faith to silence anyone that signed it.”

It could be that this stance from DJI is the symptom of a collision of cultures. Chinese companies are not known for their tolerance of dissent; freedom of speech can be seen more as a privilege than a fundamental right. That much is clear from the statement in the original NDA that inclines Finisterre to cease making “untrue or misleading statements regarding DJI, its directors, officers, employees, products and services; or this agreement..”

So we might expect some friction when dealing with a topic this sensitive. Schulman himself states in the emails that he’s having to make significant effort to “bridge the divide”. The term “huge concession” is also used at one point.

But whatever the relationship and lack of joined-up thinking between the US DJI team and its colleagues in China, much of this fuss and confusion have arisen from the fact that the Bug Bounty program was announced in a rush for PR reasons. It simply hasn’t been put together with the consideration and thought something this sensitive requires.

Final Thoughts

Since the publication of Finisterre’s account online, DJI has launched the Bug Bounty website, with terms and conditions for researchers keen to submit reports – 11 weeks after the program went live.

It’s fair to say that those terms and conditions are not quite in line with what researchers would like to see. One example is disclosure. As well as giving credit to the researcher who discovered the security bug, the company would ideally make public the neutralized threat. However:

DJI understands the importance of public disclosure of unknown or novel security flaws to build a common base of knowledge within the security community and to build a safer internet. DJI is committed to disclosing such information to the fullest extent possible. However, DJI in its sole discretion will decide when and how, and to what extent of details, to disclose to the public the bugs/vulnerabilities reported by you.

A case in point is the company’s SSL Certificate leak, which has today been announced in tandem with its disclosure in Finisterre’s report. According to a DJI statement, the manufacturer changed its SSL certificate “on September 3rd after learning that the certificate may have been compromised.”

“At this time,” the company says, “DJI has no evidence that any user information was compromised as a result of this vulnerability.”

However, by leaving the private key for its dot-com’s HTTPS certificate sitting on GitHub, DJI gave nefarious hackers all they needed to create false versions of the manufacturer’s website with the correct HTTPS certificate, before redirecting unsuspecting victims to malicious forgeries and downloads, according to The Register.

Finisterre points out in his report that a similar security lapse with the Amazon Web Services key allowed him to see “unencrypted flight logs, passports, drivers licenses, and Identification Cards,” adding up to a situation he described as a “full infrastructure compromise.”

That it took so long for the company to disclose that customers and their information were put at risk is pretty damning.

Another part of the Bounty policy which may raise an eyebrow is the section regarding indemnification:

You will defend and indemnify DJI and its officers, directors, employees, consultants, affiliates, subsidiaries and agents (together, the “DJI Entities”) from and against any and all claims, liabilities, damages, losses, and expenses, including reasonable attorneys’ fees and costs, arising out of or in any way connected with: (a) your Report; (b) your violation of any portion of these Terms, any representation, warranty, or agreement referenced in these Terms, or any applicable law or regulation; (c) your violation of any third-party rights, including any intellectual property right or publicity, confidentiality, other property, or privacy, right; or (d) any dispute between you and any third party; (e) your improper use of this Program.

This section appears to state that researchers could end up owing DJI compensation for claims, liabilities, legal fees and damages that result from successful reports. Similar text can be found in Bounty policies for Paypal, for example.

There’s also ambiguity throughout the policy that could easily fall in the company’s favor regarding the scope of where bugs can be found.

“That official announcement is full of loopholes in favor of DJI,” said David Kovar. “They’re not committing to paying for anything, they can kick you out without paying… what is out of scope is a laundry list of bugs they aren’t interested in fixing; they alone can decide that you “attacked” their infrastructure even if it is listed as “in scope”.

So where will DJI go from here? The company took an important and correct step in setting up this program, whether or not it was motivated by public relations rather than the need to prioritize security. But its implementation has been clumsy to say the least. Going forward, these missteps should be ironed out.

It should also be noted that while Finisterre and others have walked away from considerable bounties due to the terms of the NDA, there have been a number of successful payouts totalling more than $3,000.

A robust, ethical Bounty program is needed to help keep customers’ data secure while properly rewarding those who find weaknesses in DJI’s security. Let’s hope no more researchers have to walk away from DJI and its bounties in the future. A positive relationship between the two can only be a good thing.

Malek Murison is a freelance writer and editor with a passion for tech trends and innovation. He handles product reviews, major releases and keeps an eye on the enthusiast market for DroneLife.

Email Malek

Twitter:@malekmurison

Subscribe to DroneLife here.

[…] data. The company has patched security flaws found by researchers, established and developed a bug bounty program, commissioned a security audit of its app and servers, launched a local data mode to prevent […]