Our friends at Ocean Alliance have been using drones to collect samples from whales, identify them in the wild and track their movements from above. Over the summer they were in Alaska and, with the help of Intel’s algorithms, were able to spot different species in the water despite poor visibility. The Ocean Alliance team also got a chance to test out some new equipment, which included a FLIR Vue Pro, a $2,000 thermal imaging camera.

Read more: Ocean Alliance Pioneers Drone Tech in Marine Conservation

Why Use FLIR Cameras For Marine Conservation?

According to a report Ocean Alliance has sent to FLIR, the marriage of drone and thermal imaging technology has a number of potential applications for marine mammal researchers. Ocean Alliance’s Iain Kerr believes that “This technology combination holds several key advantages over both vessel and aircraft-based systems.”

“The use of drones offers a low-cost alternative to piloted aircraft and enables superior manoeuvrability and access to birds-eye observations, making it superior to vessel-based systems. As both drone and FLIR technologies progress, it is likely that researchers will discover increasingly significant applications for this technology combination.”

Read more: Ocean Alliance: Drones, Whales & Intel

Currently, Ocean Alliance has pinpointed several potential uses for thermal imaging.

The first is measuring the body temperature of a whale. For practical reasons, this kind of data isn’t yet a mainstream part of whale biology – despite it being central to keeping tabs on the health of other types of mammals. Second is the increased ability to track whales that thermal imaging provides. Day and night, any kind of observable water surface temperature change can indicate whale presence and the direction of their movement.

Then there are behavioural observations researchers can make. It’s long been assumed that plenty of social activity happens with whales once the sun goes down. Thermal imaging from above promises to illuminate some of that behaviour.

Other potential uses include determining the severity of wounds and the extent of entanglement in fishing lines, along with keeping track of population growth by counting whale blows.

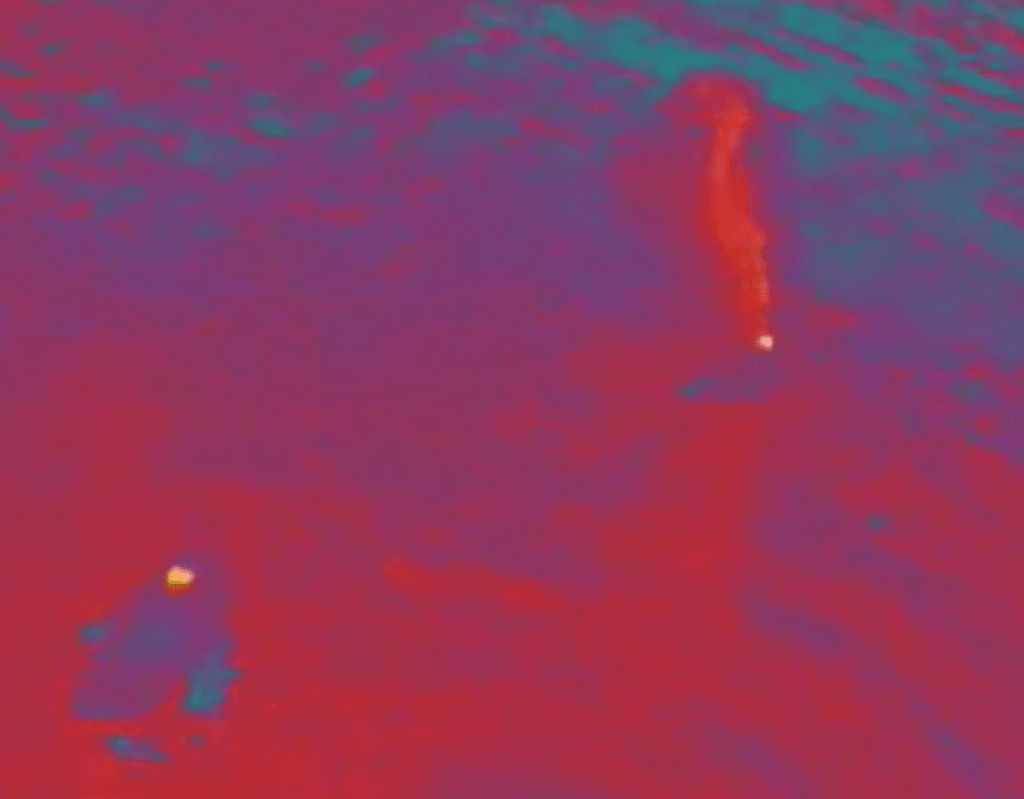

For a look at what whales look like with a thermal imaging camera, check out the video below:

In some of the clips above you’ll notice figures in the psychedelic haze. They may not look like whales, but they are. Kind of. It’s probably more accurate to say that what you’re seeing is the ‘footprints’ of the whales. FLIR cannot see through glass or water, but it can see where cold water gets pushed up by the whale’s passage. This is a phenomenon that was invisible to the naked eye and the rest of the team’s equipment.

MIDAR – The Next Step

Because traditional thermal imaging doesn’t reach below the surface of the water, Ocean Alliance is now exploring the possibility of MIDAR technology to get a better understanding of what happens in the deep blue. Until that comes to fruition, underwater imaging may remain just out of reach.

You often hear that there are parts of the solar system that have been more thoroughly explored than the depths of our oceans. Weirdly, with the help of drones and MIDAR sensors, that might not be the case for much longer.

Thanks to Ocean Alliance for supplying the FLIR footage and thoughts on the use of thermal imaging in marine conservation.

Malek Murison is a freelance writer and editor with a passion for tech trends and innovation. He handles product reviews, major releases and keeps an eye on the enthusiast market for DroneLife.

Email Malek

Twitter:@malekmurison

Subscribe to DroneLife here.